This article is published in Aviation Week & Space Technology and is free to read until May 10, 2024. If you want to read more articles from this publication, please click the link to subscribe.

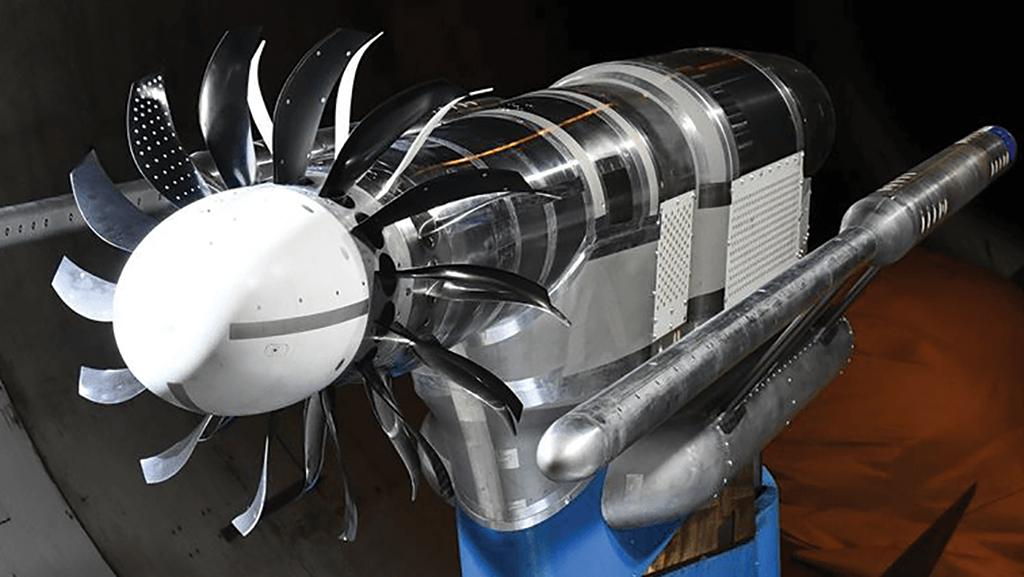

Tests of the GE-Safran RISE—including wind tunnel evaluation of the concept’s scaled open fan—are stepping up in 2024.

The past month demonstrated vividly that Boeing and GE—America’s two most important aerospace companies—are on different paths. The issues at Boeing are well-documented and will lead to a wholesale change in leadership with CEO David Calhoun stepping down by year-end. In contrast, under the leadership of Larry Culp, GE is experiencing a metamorphosis, rising from the abyss to become the best-positioned aerospace pure-play business on the planet. With Boeing approaching a reset, this raises the question: What can it learn from GE?

Quality is a bottoms-up outcome. The door-plug blowout on a new Alaska Airlines Boeing 737 MAX in January highlighted what most of the industry already knew: Boeing has a quality problem. Chief Financial Officer Brian West admitted the OEM had prioritized the movement of airplanes through the factory over doing it right. There are schisms between factory workers and supervisors and between the C-suite and operations. Boeing brought in U.S. Navy Adm. (ret.) Kirkland Donald and a team of outside experts to review its quality control processes, but its problems stem from a broken culture. In contrast, GE’s value system under Culp begins with safety, quality, delivery and cost before all else. These are values he applied as Danaher’s CEO to make it one of the world’s leanest and best-run companies. GE Aerospace just rolled out an operating model called Flight Deck to imbue and reinforce these values throughout the organization.

Depth before breadth. Boeing’s business has four major legs: commercial aircraft, defense aircraft, space and services. While all are part of the aerospace industry, the reality is that building space launch vehicles has little to do with making commercial jetliners. Ditto with some of its services such as parts distribution. Its vast portfolio needs purging while its Washington headquarters—geographically removed from core operations—needs to be reconnected. In contrast, GE just jettisoned its century-old conglomerate business model to become an aeroengine and systems pure-play company. Rather than decamping to a remote headquarters, Culp’s next act is to immerse himself in the business, its customers and its critical functions. He favors organic growth over acquisitions and stated that he would rather be part of a great company than a big company.

Invest in the future. Boeing’s independent research and development expenditures are modest, its single-aisle flagship is based on a 1960s-era design, and it has promised no new aircraft for the foreseeable future. At the end of last year, it eliminated its corporate strategy and competitive intelligence functions, and its sustainable aviation strategy is murky. GE is investing 6-8% of revenue in product development and is engaged with its CFM joint venture partner Safran in the Revolutionary Innovation for Sustainable Aviation (RISE) program, the largest technology development initiative in its history. RISE includes a radical new open fan architecture as well as investments in alternative propulsion technologies (hydrogen, hybrid electric, materials) and adaptive-cycle engines. Culp believes in the value of strategic planning and making investments to spur organic growth.

Practice humility. Boeing has spent the last decade engaged in a counterproductive war with its suppliers and employees. GE did the same under Jack Welch and, to a lesser extent, Jeff Immelt. Culp has broken with the past, elevating humility to a core value for his team. “Lead with humility, transparency and focus” is one of his mantras. Many suppliers have yet to see a significant GE mindset change, but with Culp and his leadership team 100% focused on aerospace, change is inevitable. A good first step would be to alter the punishing 120-day payment terms GE and other major OEMs impose on their cash-strapped suppliers.

Goodbye “shareholders first.” Boeing changed its focus from a product and engineering culture to a “shareholders first” value system over the last two decades. The manufacturer plowed $68 billion into dividends and share buybacks over the last decade while execution, quality and product development languished. This approach doesn’t work in a long-cycle business like aerospace, as I argued in this column four years ago (AW&ST March 23-April 5, 2020, p. 10). GE behaved similarly in the past, but Culp has flipped the script. He believes an OEM should first build a great product and delight the customer, then take care of its employees, and the share price will follow.

These five attributes highlight why Culp is a transformational leader and why his company is arguably the industry’s best hope to lead it out of a dark “shareholders first” chapter in its history. Boeing’s new leaders would be wise to study GE’s metamorphosis.

Comments